Tuesday,

March 1, 2016

9:30am

From 1929 to 1939, the Western world was plunged into the deepest economic downturn in modern history. Our March exhibit delves into how Worthington weathered this grim decade.

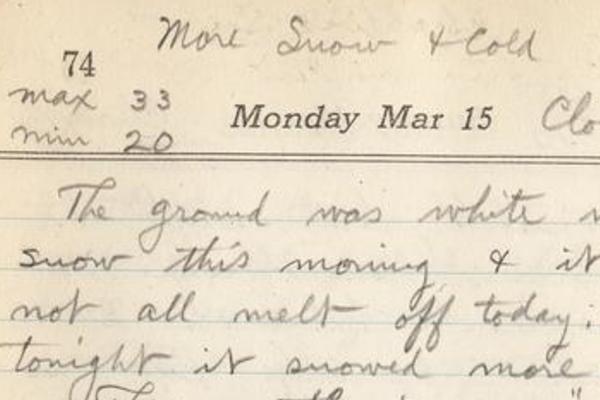

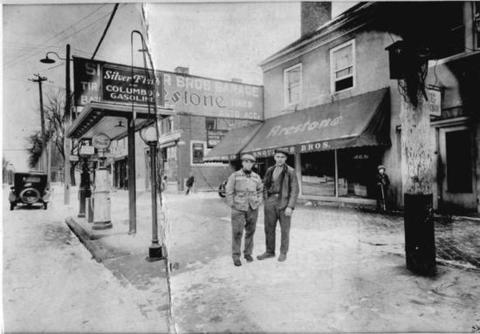

Worthington’s slow, but steady, growth in the early 20th century lurched to a virtual halt in 1929 with the sudden crash of the stock market. By 1920, the village had achieved some major milestones: water, sewer and electric service had all been installed and, by the time of the crash, it was beginning to be considered a pleasant retreat from city life and an easy commute to Columbus via the Columbus, Delaware & Marion interurban rail line.

However, for a number of local ventures, the timing of the economic collapse couldn’t have been worse. By 1930, the Van De-Boe Hager Company had just finished installing water, electric and sewage lines for an upscale housing development, and had just completed building a model home on Crescent Street in the project they named “Riverlea.” The Van De-Boe Hager Company had previously developed some high-end neighborhoods in Beechwold, but unpaid taxes forced the sale of unsold lots in Riverlea at very low prices in 1939.

Likewise, sections of the Colonial Hills neighborhood closest to High Street were first platted in 1927, but development stalled in the following decade. The last section, near Selby Boulevard, was not platted until 1942.

In another example of spectacularly bad timing, voters turned down a school bond issue on the November 5, 1929, ballot, less than a week after the October 29 stock market crash. Elementary- and middle-school students would have to continue to squeeze into a school built in 1893 until it was torn down and replaced in 1938 by the building now known as Kilbourne Middle School.

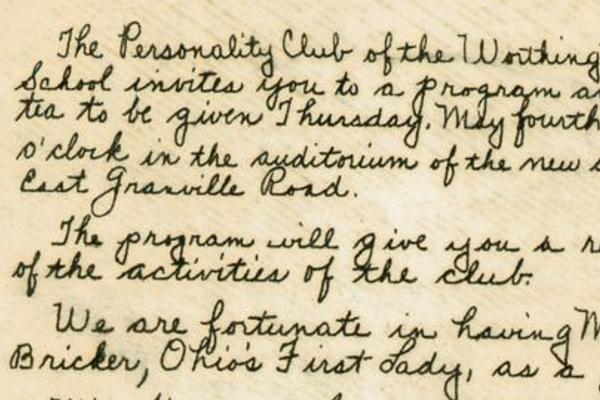

Signs of poverty were certainly clear to a Worthington mother who established the Personality Club in 1937 after learning that some high school girls didn’t attend a school party because they lacked nice enough dresses. A group of mothers began to meet weekly to repair and alter older clothes and sew new dresses. The club went on to provide etiquette classes, dancing lessons and presentations on “charm and personality” for high school girls and boys. The Personality Club lives on today after being reorganized and refocused as the Activity Club in later decades.

There was plenty of hardship for area farmers as well. According to a report published in the "Worthington News" in 1933, Ohio’s grain crop of 1931—the largest ever—sold for the lowest price since recordkeeping began. Ohio wheat, which sold for $1.02 per bushel in 1880, sold for only 50 cents per bushel in 1931. The Brown Fruit Farm hired migrant workers at $1 for eight hours of work, and at times there was not enough work for all. At the end of the day, harvested fruit had to be locked up to protect it from “raiders” driving through the orchard hoping to steal it.

We have an exceptionally good pictorial record of rural central Ohio, thanks to the social realist painter Ben Shahn, who spent the summer of 1938 photographing the region for the Farm Security Administration. His photos of Worthington and surrounding farms can be found at the Library of Congress. The Worthington post office, which was built in the 1920s, hosts another New Deal project, the terra cotta relief titled “The Scioto Company Settler.” It was made in 1938 by Ohio artist Vernon Carlock as part of the Public Works of Art Project.

World War II and its aftermath primed Worthington for the explosive growth it experienced in the 1950s and ‘60s. The Great Depression served as a difficult, decade-long pause between Worthington’s past as a little farm town and its future as an inner-ring suburb of Columbus.