Monday,

December 30, 2024

10:22am

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the polio vaccine. Our January exhibit reflects on the local impact of this medical breakthrough.

In the early 1950s, August was a time for children to savor the last days of summer before school began. For parents, August and September meant the peak of polio, an incurable virus so frightening it could haunt a parent's dreams.

And then, within the space of a few years, the nightmare went away. Worthington's first- and second-graders lined up in April 1955 to receive a vaccine that would protect them from poliomyelitis-- a virus that attacked brains and spinal cords. A nationwide vaccine campaign would finally free Worthington and the country from this plague after years of extraordinary community organization and medical research.

The vaccine came too late for Worthington first-grade teacher Marjorie Willock. She fell ill in late September 1952 during Franklin County's last big polio epidemic. She lived nearly half her life in an iron lung. Her tragic story of paralysis and perseverance could describe the experiences of many polio survivors.

In a heart-wrenching letter published in the "Worthington News," she wrote from her hospital bed to her soon-to-be second-grade students at the end of the 1953 school year:

…Even though we have been apart, I have thought a great deal about you, wondering about your school activities and how much you have grown since I last saw you. I know that many of my first grade friends will be losing their baby teeth, but that is something we all experience when we are six years old.

While you have been working hard at your lessons, I, too, have had work to do. I am trying to learn how to breathe again. You see Polio has put most of my muscles to sleep-- my breathing muscles, my walking muscles, and my arm muscles. It takes a long time for them to wake up. Wish I could show you my iron lung, rocking bed, and wheel chair that I use every day. Then you would understand more about Polio.

Because I love each of you so very much, I want you to promise me something. I want you to have a happy summer with your family and friends, but do not get overtired. Listen to mother and daddy and if it is at all possible take a nap each afternoon. You must know that God does not want us to have Polio, but He does want us to take care of our wonderful bodies. Because I had Polio when I was with you last September, the doctors tell me that most of you probably will never have it.

I miss your letters, please write to me this summer. It is next best to being with you.

My love,

Miss Willock

Although polio infections could be fairly mild, for some patients the outcome was paralysis and death. Polio struck children and adults alike. The quintessential image, repeated in newspaper stories and fundraising appeals, portrayed an innocent child playing happily; within 24 hours the same adorable five-year-old would be unable to move, encased in a neck-to-toe "iron lung" metal cylinder that kept the patient breathing by compressing the paralyzed lungs. Recovery could take years. Survivors, most famously President Franklin D. Roosevelt, might need leg braces, crutches, wheelchairs or breathing apparatus for the rest of their lives.

The epidemic that swept up Willock took more Ohio victims in 1952 than any year before or since. Nationwide, almost 58,000 Americans were infected; 21,000 were completely or partially paralyzed, and more than 3,000 people died of the illness that year. In Franklin County, 123 cases were reported in 1952, compared to 54 in 1951.

Three years later, there was still no cure for polio. However, during 1954-55, Dr. Jonas Salk ran double-blind field trials for a promising vaccine. About 1.8 million American first-, second- and third-graders-- children thought to be at the most vulnerable age-- participated in this huge study. When the results were announced on April 12, 1955, it was front page news nationwide. "The Columbus Dispatch" ran the banner headline, "Polio Whipped; Vaccine 80-90% Effective." Joy and relief-- and a massive mobilization of health care workers and volunteers-- led to a swift community response. Within five days, on Monday morning, April 18, the first- and second-graders of Sharon, Homedale, Worthington Elementary, Flint, North Perry, St. Michael and Seventh Day Adventist schools found themselves lined up in the Worthington Elementary gymnasium receiving the first of three polio shots. In the coming years, cases of paralytic polio fell to fewer than two per 100,000 people in the United States.

When an improved vaccine became available in 1962, Worthington mobilized again with "Sabin on Sunday" events. Named for polio researcher Albert Sabin, "Sabin Stations" at Worthington High School, Colonial Hills Elementary, St. Michael School and Linworth Elementary dispensed an oral dose of the new vaccine. The first of three doses were administered on Sunday, September 30. Organizers suggested a 25-cent donation, but the vaccine was free to all who requested it.

It is hard to exaggerate the devastation of polio. In 1954, after nearly two years in an iron lung at Children's Hospital (all local polio patients were treated there) and at a specialized clinic in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Willock, 27, finally returned to her home on Olentangy River Road just south of Worthington. Her parents had converted their porch to house the former teacher's iron lung, a rocking bed and respirator equipment. She used an iron lung and respirator at all times until her death in 1975 at age 49. She was able to go outside briefly once or twice a year. She could speak, turn her head and move three fingers of her right hand. The rest of her body was immobile. Her companion and live-in nurse Elfriede Drescher wrote "Sufficient Grace," a book describing Willock's 23-year struggle, in 1987.

The "Worthington News" followed the progress of local polio cases. Long hospital stays and treatments far from home must have increased patients’ sense of isolation and fear of being forgotten. When eight-year-old Jimmy Spahn returned to Children's Hospital with the flu in 1957, the "News" reported "Jimmy was a victim of polio four years ago and has made a courageous fight to overcome the effects of the disease. He has attended school and the Powell Sunday School whenever possible. Cards sent to him at the hospital would be greatly appreciated." Young Steve Wren was able to come home from Children’s Hospital just long enough to enjoy Beggar's Night, but had to return to the hospital and hoped to be back home by Christmas.

Neither the long, ongoing care of polio victims nor the massive research investment needed to find and produce a vaccine would have been possible without the March of Dimes. This fundraising appeal from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis raised $250 million between 1951 and 1955, when the polio epidemic was at its peak. Since its inception in 1938, the organization provided $315 million for the care and rehabilitation of 325,000 polio survivors, $55 million on research and vaccine development and $33 million on training for medical personnel.

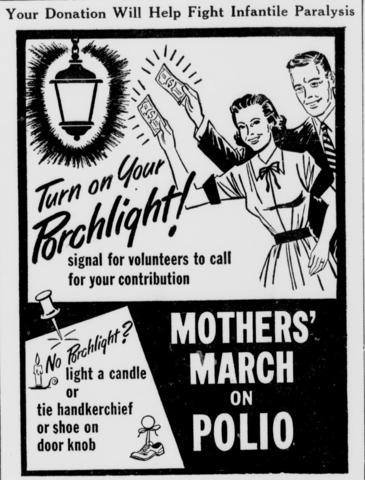

In 1954, Worthington students raised more than $300, which they presented to the Franklin County Chapter of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in Willock's name. Beginning in 1953, the annual March of Dimes campaign in Worthington and Sharon Township culminated in a "Mothers March on Polio" on January 29. Worthington residents were instructed to turn on a porch light or tie a shoe or handkerchief to their doorknob between 7-8 p.m. that night. A local mother would come to the house and collect a donation, no matter how small, for the campaign. In 1955, the Mothers March raised $6,000 during the one-hour fund drive in Worthington and Sharon Township. Approximately 350 volunteers participated and other community organizations contributed as well.

At a time when so much was unknown about the threat of polio, the nation came together to support its children, its medical professionals and its communities in one of the most effective public health campaigns in its history.