Wednesday,

June 1, 2022

9:30am

Juneteenth celebrates the end of slavery in the United States. It's been observed on June 19 since 1866, and in 2021 was recognized as a federal holiday. Step inside to learn more about the holiday, as well as Worthington's response to slavery and its nearly 160-year aftermath.

In June 1865, two months after the surrender of the Confederate Army and two years after the Emancipation Proclamation, 250,000 Black people remained enslaved in Texas. On June 19, Union troops arrived at Galveston to share "General Order No. 3," which states, "The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free."

The following year, June 19, 1866, saw the first large celebration known as Juneteenth, which was carried on for the rest of the century and into the next. Observance of the holiday waned in decades during the mid-20th century, as Black people focused on expansion of their civil rights, but revived in the late 20th century.

As of June 2022, no Juneteenth celebrations are documented in Worthington Memory; however, the history of African Americans in Worthington dates nearly to its beginning. In 1807, four years after Worthington's founding, there are records of payments made to "Black Daniel" for working in Amos Maxfield's brickyard. In 1856, when the country remained in turmoil over the issue of slavery, former enslaved people from Virginia became the first African Americans to buy their own home here. Henry and Dolly Turk purchased the house that still stands at 108 W. New England Avenue, and their family owned it until 1895. Henry had bought his wife's freedom from enslavement in 1838 and, according to an account by Lovisa Wright in 1904, "Henry and Dolly Turk were liked by all."

It’s also possible that, before 1865, hundreds of enslaved people passed through Worthington on their way to seek freedom in Canada. Worthington has long been recognized as having two stops on the Underground Railroad: Ansel Mattoon's house and Ozem Gardner's farmstead in Flint. Oral history has it that Gardner assisted more than 200 enslaved people on their journey.

Although Worthington celebrates its past as an anti-slavery community, throughout its history it has, like the rest of the U.S., grappled with the aftermath of slavery and ever-present racism. A stark example of this is the restrictive covenants found in the deeds of houses in neighborhoods that sprang up throughout Worthington in the post-World War II boom. A "restrictive covenant" is a legally binding contract in the deed that dictates what homeowners may and may not do. One example of a restrictive covenant from Colonial Hills reads "No part of said addition or any buildings there on shall be owned, leased to or occupied by, any person other than one of the Caucasian race…" The clause makes an exception for domestic servants.

Riverlea presented another example of this type of exclusion. A February 11, 1987, "Columbus Dispatch" article interviews Harold Jones, associate pastor of the St. John’s A.M.E. Church, who describes the neighborhood's segregation: “One of the ironies, Mr. Jones said, is that James Birkhead, one of the founders of St. John A.M.E. Church, owned a 17-acre farm that became part of Riverlea. The village on the southern edge of Worthington was laid out in 1929, three years after Birkhead died, but not developed until after the Depression and began to boom after World War II. Here was a land a black man had owned that was closed to blacks." Harold Jones and his wife, Juanita, went on to help found the Worthington Human Relations Council in 1963 to address issues of segregation in housing.

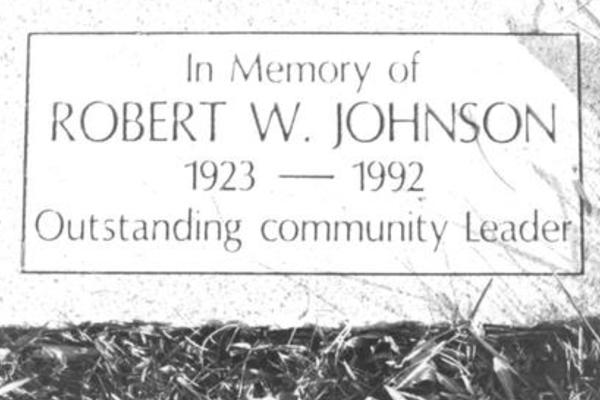

In 1958, Robert and Vera Johnson, a Black couple, purchased 12 acres along Flint Road that would become Flintridge Terrace. The couple methodically laid out a community plan for a neighborhood where Black people could own homes in Worthington. The neighborhood’s history and development is described in detail in "Linking Past to Present: An Historical Account of Flintridge Terrace & Its Surrounding Areas."

In 2020, the U.S. finally began to reckon with another aspect of institutionalized racism and the legacy of slavery: police brutality toward Black people. Following the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota, a vast protest movement rose up in all 50 states and around the world. Residents of Worthington joined in several protests throughout the summer. In marches and demonstrations, participants carried signs, played music and called out their support of the Black Lives Matter movement. They laid face-down on the sidewalk with their arms behind their backs for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the length of time that police officer Derek Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd's neck (bodycam footage later revealed the actual time to be nine minutes, 30 seconds).

2021 saw a first in Worthington's history-- the community’s first official Juneteenth celebration. As stated on the City of Worthington's website, "On this Juneteenth holiday, celebrated on June 19 to commemorate the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States, we recognize that 156 years later their ancestors and other people of color are still faced with unequal opportunity and racial discrimination. The Worthington community is committed to condemning racism, working to promote racial equity, and participating in the community dialogue to bring equal treatment and opportunity to all people."

The Juneteenth tradition continues in Worthington this year with a celebration on Saturday, June 18 in observance of the holiday the following day. It’s a time to reflect, learn and celebrate.