Friday,

May 1, 2020

9:30am

As the final ferocious battles of World War I raged through the fall of 1918, distracted Worthington residents fretted about the fates of the some 50 local men who fought overseas. Another invisible, but just as deadly, foe would soon amplify their fears. Our May exhibit revisits the flu pandemic of 1918.

In late September, some central Ohio residents began to die of what seemed to be a virulent form of pneumonia. This mysterious influenza first appeared in the spring of 1918 in the crowded barracks of U.S. military camps. It could kill with frightening speed. Charles E. Robbins of Worthington, age 40, died in France in September 1918. According to the "Columbus Evening Dispatch," "Mr. Robbins had been ill less than a half hour" when he died. He had shipped out from New York City in January 1918 and served as an army private in the Quartermaster Corps Mechanical Repair Shop. He left behind two children. His parents did not learn of his death for a month. There is a memorial to him in Walnut Grove Cemetery.

Worthington residents Mr. and Mrs. B. Hermman must have been distraught to receive a letter from their son, Bernard, in late November. By the time the letter arrived, the fighting had ceased, thanks to the November 11 Armistice. Bernard wrote he was recovering from a badly injured arm in a French hospital. Surely his parents feared that, though he had survived the war, he might lose his life to the dreaded influenza. However, he appears to have survived as he was honorably discharged in July 1919. He was awarded the French Croix de Guerre with silver star for his service as a Marine who fought in some of the biggest final battles of the war.

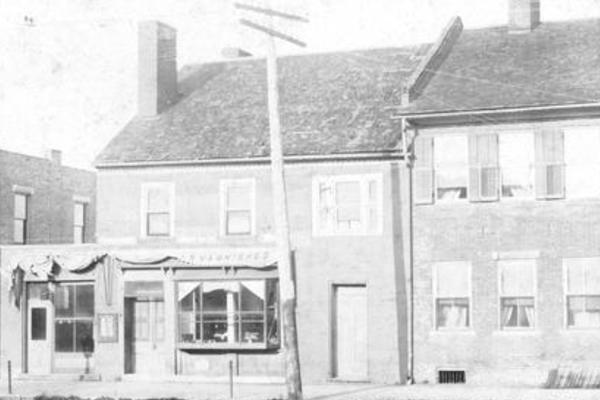

Lawrence G. Leasure, a 24-year-old Worthington man, was not so fortunate. Leasure enlisted in the Army on September 27. Less than a month, later he was dead. He died October 22, 1918, from influenza at the Columbus Army barracks. It seems unlikely he ever left Franklin County during his brief military service. At the time, the Columbus barracks (later renamed Fort Hayes) served as a large recruiting, intake and training facility. Lawrence grew up in Worthington, the son Harry and Anna Leasure. His father owned a drug store on the southwest corner of West New England Avenue and High Street and was active in Worthington civic organizations. Leasure had married Helen Moore two years before, and they lived in Worthington with his parents. He is buried at Walnut Grove Cemetery.

The same day Leasure died, the "Columbus Evening Dispatch" published an obituary for another Worthington soldier. Harold F. Case, age 24, died at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, where he was enrolled in officer training camp. His body was returned for burial in Worthington.

More U.S. soldiers died of the new "Spanish flu" than perished in the actual fighting. All told, an estimated 43,000 American troops died of the disease. At Camp Sherman, located just outside Chillicothe and one of the largest military camps in the U.S., the virus infected thousands of young soldiers and staff. Twelve hundred soldiers died there during a few weeks that October.

The flu, which may have originated here in the U.S., then shipped off to Europe with the troops, only to return in even more virulent form via the ports of America's East Coast, began to show up in central Ohio's civilian population in September 1918.

At the time, Worthington was still a village surrounded by farms. According to the 1920 Census, the village population was approximately 700, with only about 2,300 residents in all of Sharon Township. But Worthington's proximity to Columbus meant it was not isolated from the conditions that made the new influenza spread so rapidly.

An interurban electric trolley connected Columbus to Worthington's village green, allowing Worthington residents to commute to Columbus and city residents to enjoy a day in the country by riding the trolley all the way to Delaware and Marion, with stops along the way. The interurban rail company encouraged Columbus residents to hop on the trolley and stop for a meal at the Hotel Central (the Worthington Inn); stroll around Worthington's small village; cool off at Glenmary Park, near present-day Flint Road with its dance pavilion and outdoor entertainments; or pick apples at orchards of the Brown Fruit Farm. Additionally, up to 200 employees may have traveled daily to the Brunt Tile and Porcelain Company via the Chaseland interurban stop just south of Worthington. This large factory was considered state-of-the-art at the time, and manufactured mosaic floor tile and porcelain insulators used in electric power transmissions. The facility was located more or less where Lincoln Avenue and Sinclair Road meet at the railroad tracks today. A more genteel country retreat could be found at the Harding psychiatric hospital on the eastern edge of the village.

In late September 1918, the first recognized cases of the flu arrived in Columbus. At the time, the "Columbus Evening Dispatch" headlines blared news of battles and war casualties, with influenza's arrival a side note to the serious international conflict.

On October 3, Columbus Health Commissioner Dr. Louis Kahn told the "Dispatch," "There is no need to worry as far as Columbus is concerned. The epidemic appears to be at its peak and we can look for a lessening of the number of cases within a few days." However, he advised avoiding crowds and covering your mouth when you sneeze or cough. Two days later, he reminded residents to avoid crowds, stay home if they were sick and wear a mask if taking care of someone who was sick.

On October 7, Dr. Kahn met with Columbus public school officials. He felt closing schools would not be necessary, but he left the final decision to school authorities. According to the "Dispatch," "His [Kahn's] refusal to 'throw a scare' into the public last week, has been productive of good results, in that it prevented a general fright." One day later, Ohio recorded 25,000 influenza cases.

Within the next two days, the Ohio Department of Health reported thousands more were sick. By October 9, approximately 700 soldiers had died at Camp Sherman. In one 24-hour period that week, 125 soldiers died. Some schools began to close in Franklin County, as did Ohio University, Miami University and Ohio Wesleyan University.

At some point around this time, Worthington schools also closed, though there is no available record of the exact date. Ohio's department of health had ordered all public gathering places to close beginning October 12 if and when "the disease makes an appearance," to be determined by local officials. According to acting health commissioner for Ohio James E. Bauman, "it's more a suggestion to local officials than a mandatory order." This somewhat contradictory "order" included movie theaters, theaters, schools, churches and indoor meetings of all kinds. Saloons, cigar stores, pool rooms, drug stores and grocery stores were exempt. The order applied to all communities with a population over 3,000, so the village of Worthington would not necessarily have been required to comply.

By this point, an Ohio health department official reported there were at least 40,000 recorded cases in the state, and many more unreported. Columbus reported 267 cases of influenza. The Ohio State University closed and students were sent home. Local ministers agreed to cancel all Sunday church services.

However, not everyone seemed to feel the same sense of urgency. The Columbus Chamber of Commerce urged Dr. Kahn, the Columbus health officer, to make an exception for two big events. The Chamber rationalized that a musical event at which "only the best class of people will attend the concert and will not be as liable to carry germs of the influenza as might be true with some other forms of entertainment." Secondly, a national dairy show should go on because it would be held outdoors and therefore not likely to spread germs. Local Methodist ministers petitioned Columbus health officials to close saloons as well during the epidemic because "the saloon is one of the principal sources of disease of all kinds for the reason that men congregate there in great numbers, drinking from glasses used by others that have not been properly sterilized." However, despite the argument it was unfair to close churches and allow saloons to stay open, saloons often provided an essential service: inexpensive meals for low-wage workers.

Columbus schools closed October 14.

By October 17, there were 70,000 reported cases in Ohio, and no sign the epidemic was slowing down. State health commissioner James Bauman expected the infection rate to peak the following week. The total number of cases in Columbus was 1,216.

Two days later, October 19, there were 90,000 cases in Ohio; 1,544 in Columbus. All pool rooms closed by order of the Columbus health officer. Bowling alleys, card rooms, lodges and clubs also closed. Health inspectors were given the option to close saloons, cigar stores, soda fountains and other locales if rules for ventilation and crowd control were not strictly followed.

On October 20, Miss Louise Wood, a high school teacher in Lima, returned to Worthington to stay with her parents until schools reopened.

On October 21, the City of Columbus Board of Health banned all indoor and outdoor gatherings. Residents were urged not to visit relatives and friends. People should avoid public transportation if possible and walk to work. Street cars were required to have all windows open, and saloons must keep all doors and windows open: "No loafing or loitering." Individuals could be fined $100 for violating any of these orders.

According to Ohio acting health commissioner Bauman, 150,000 cases statewide had been reported to the department and possibly that many more remained unreported as of October 26. To date, 2,650 cases were reported in Columbus.

"Columbus is the brightest spot on the map." As of October 30, the infection rate in Columbus seemed to be slowing as the number of new cases declined, according to Dr. Kahn. However, he told the "Dispatch" he was not ready to lift quarantine, and all Halloween parties and other gatherings were forbidden.

On October 31, Ohio's health department authorized local health officials to lift restrictions when they judged it safe to do so. Dr. Kahn in Columbus reported he was not ready yet to remove the ban.

Dr. Kahn announced theaters and movie theaters could reopen November 10. Football games could resume Saturday, the 9th. However, all schools, public and parochial, must remain closed.

Columbus schools opened again November 18 with the restriction that no child could attend if any family member was sick with influenza.

Meanwhile, back in Worthington, on November 17 the "Dispatch" reported that Dr. A.B. McConagha had been commissioned as an officer in the medical corps and was awaiting news of where he would be posted. Dr. McConagha practiced medicine in the buildings that fronted the southeast corner of the Village Green, where he had a private hospital in his house. Having been called up six days after the Armistice, Dr. McConagha's time in the military appears to have been brief; according to the "Dispatch" society page, he and his wife were entertaining guests in Worthington for New Year’s Day.

By Thanksgiving, it was clear health officials had been too hasty in reopening schools and businesses. On December 3, with 10,493 students absent from school and 32 teachers sick with influenza, Columbus officials decided all city schools must close, possibly through the end of December. Additionally, all children under 12 would not be permitted in stores or on street cars, making it difficult for parents who relied on their children to run errands for them.

Influenza infections may have peaked in Columbus, but not so in Worthington. Public schools, Sunday schools and all public gatherings were once again banned. On November 28, the "Dispatch" reported there were more than 100 cases in Worthington and vicinity. Fourteen Worthington High School sophomores were infected. Miss Helen Robinson, Worthington High School teacher; her sister, Miss Lucille Robinson, an Ohio State University faculty member; and Professor H.C. Fickell, superintendent of Perry Township schools, were all stricken with influenza. Henry Prosser, age 60, died of influenza at his home near Worthington.

Influenza continued to wreck the lives of Worthington residents, particularly mothers who nursed family members before becoming ill themselves. On December 12, the "Dispatch" reported Mrs. Lewis Davis of Worthington had traveled to Elyria to be at her daughter's deathbed, while two grandchildren were also critically ill. Davis had recently returned home from nursing the families of her two other daughters in Linworth. As New Year's Day approached, Mrs. C.E. Hard of Worthington cared for her daughter-in-law and two grandchildren until their mother died and Hard herself became so ill with influenza she could not continue.

Influenza brought additional complications. On December 29, the R.B. Turner family and their guests barely made it out of their Worthington house alive after it caught fire. According to the "Dispatch," the Worthington Fire Department was helpless and unable to assist because the village engineer had been ill for several days and unable to keep the village water tank full.

The new year brought more misery. On January 10, 1919, Lydia Smiley, a 74-year-old widow in Worthington, died of influenza. Worthington residents were still suffering in March. Dr. Edgar Burke, age 37, died at home in Worthington. His wife was also critically ill, according to the "Dispatch." Dr. Burke was a veterinarian at the huge Hartman stock farm on state Route 23 south of Columbus.

Surely one of the most harrowing stories involved the Samuel Penn family of Worthington. On March 14, 1919, the "Dispatch" reported both parents were ill, along with all four of their children. Two of the children had scarlet fever along with influenza. Penn's mother, who had been nursing the family, also came down with the flu. On March 24, the "Dispatch" followed up to report that four-year-old Bertha Penn had first contracted scarlet fever, then influenza and pneumonia, before lapsing into "sleeping sickness" for more than a week.

Old newspapers tell only part of any story. Every Sunday edition of the "Dispatch" during this period featured an Out-of-Town Society column, which always included news from Worthington. During the fall and winter of 1918-19, half a million Americans died of a mysterious new infection, the ferocious battles of World War I came to an end and Ohioans debated banning the sale of alcohol. But to judge by the society page, life in Worthington seemed to suffer no significant slowdown in travel and social events. The Worthington society news continued to share copious descriptions of luncheon and dinner parties, hosts and guests, visits from friends and relations and party decoration details. On New Year's Day 1919, the Hotel Central hosted a Peace Dance for 70 guests. The "Dispatch" did not report how many party guests fell ill in the first few weeks of the new year.

Note: This information was compiled with limited access to some archival resources and may be revised at a future date.